By:

Catarina Conti, Senior Editor

16 May 2016 – More developments last week in the Stored Communications Act case we have been following, In re: Grand Jury Subpoena to Facebook, A New York federal judge rejected the government’s bid to block Facebook and potentially other service providers from disclosing the existence of 15 separate grand jury subpoenas for customer data, ruling that prosecutors’ “boilerplate” assertions weren’t enough to justify the gag orders, but gave them an opportunity to try again.

In his order, U.S. Magistrate Judge James Orenstein ruled on 15 separate applications recently filed by the government that asked the court to require service providers to not disclose the existence of grand jury subpoenas for customer information that they had received. Thirteen of the subpoenas were served on “service providers” that the order didn’t identify, while the remaining two were directed specifically at Facebook Inc., according to the order.

Denying all 15 requests, the judge concluded that the government had failed to provide enough details to allow him to determine whether or not the nondisclosure orders were warranted under Section 2705(b) of the Stored Communications Act, which allows courts to issue such gag orders when there is reason to believe that a failure to do so would seriously jeopardize an investigation:

“The government cannot, consistent with the statute, obtain an order that constrains freedom of service providers to disclose information to their customers without making a particularized showing of need. The boilerplate assertions set forth in the government’s applications do not make such a showing.”

Despite his conclusion, the judge did give prosecutors another chance by denying their applications without prejudice to renew their requests “on the strength of additional facts about each investigation that permit a finding that disclosure of a subpoena will result in an identifiable form of harm to the investigation.”

In all 15 applications, the government had argued that the nondisclosure orders were necessary because the subpoenas related to an “ongoing criminal investigation that is neither public nor known to all of the targets of the investigation,” and that disclosure of its existence may alert the targets to the ongoing investigation and would seriously impede the probe by giving the targets the opportunity to flee, destroy evidence or change their behavior.

But Judge Orenstein wrote that he “respectfully disagree[d]” with the government’s reasoning, pointing to the fact that the Stored Communications Act requires courts to find that the revelation of a subpoena “will result in” the endangerment of a life, flight from prosecution, destruction of evidence, witness intimidation or the significant impediment of a probe:

“While it is unquestionably true that a service provider’s disclosure of a subpoena for customer records ‘may’ alert the target of an investigation to its existence, it is just as true that disclosure may not have that effect. Thus, before I can conclude that disclosure ‘will’ result in such harm as the statute requires, I must have information about the relationship, if any, between the customer whose records are sought and any target of the investigation.”

The judge also concluded that prosecutors had failed to sufficiently detail whether or not the targets of the probe had the ability or incentive to flee or destroy evidence.

While Judge Orenstein applied the same reasoning in shutting down the two Facebook-specific applications, he additionally rejected the bids on the grounds that the government had not adequately advanced its request made only in the Facebook applications to prohibit the social networking giant from taking “certain actions” that the government claims would indirectly, but effectively, alert targets to the existence of the probe:

“The government has stated no more than that Facebook has taken such actions previously in response to receiving subpoenas. What the government has not told me is whether Facebook routinely does so in response to every subpoena, or only in certain circumstances, and whether, and under what circumstances, Facebook takes the same actions even in the absence of receiving a subpoena.”

Without this information, Judge Orenstein concluded that he could not determine whether the indirect disclosures would harm the investigation, or whether they were harmless “prophylactic measure[s]” that wouldn’t reveal the existence of the subpoena and would allow Facebook to take actions such as preventing a customer from using its service to harm others.

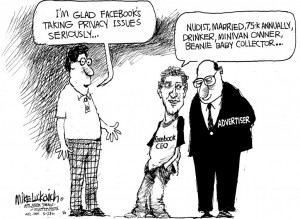

A Facebook spokesman declined to comment on the judge’s ruling Friday. However, Facebook’s public policy for dealing with law enforcement requests … as noted on its website …. is “to notify people who use our service of requests for their information prior to disclosure unless we are prohibited by law from doing so or in exceptional circumstances.”

Interesting note: last week’s ruling marks the second time this year that Judge Orenstein has ruled against the government’s attempt to compel a service provider to assist it with a criminal probe. In February, the judge roundly rejected the government’s contention that under the All Writs Act of 1789, the court could require Apple to help the government break into confessed drug dealer Jun Feng’s iPhone 5S.

That decision, along with a ruling by a California magistrate judge weeks earlier in another case involving Apple that reached the opposite conclusion, helped spark a public debate over how far companies must go to assist law enforcement, a fight that was further stoked last month when Microsoft filed a suit challenging the government’s ability to force service providers to keep customers in the dark about law enforcement demands to access user data.