It’s worth making the point again about TikTok: it’s utterly unlike the networks that we – well, adults – think we’re used to. It’s wiping the floor with Facebook for attention. I’d guess nobody could describe exactly how its algorithm functions; only what the desired outcomes it aims for are.

BY:

Eric De Grasse

Chief Technology Officer

PROJECT COUNSEL MEDIA

23 May 2022 (Berlin, German) – Elon Musk’s manic toggling between shit-posting and falsehoods have distracted us from what is the ascendant tech firm of 2022. TikTok now commands more attention per user than Facebook and Instagram combined. Downloaded more often than any other app for each of the past five quarters, it was the world’s most visited site in 2021. TikTok has 1.6 billion monthly active users – more than Twitter, Snapchat, and LinkedIn combined.

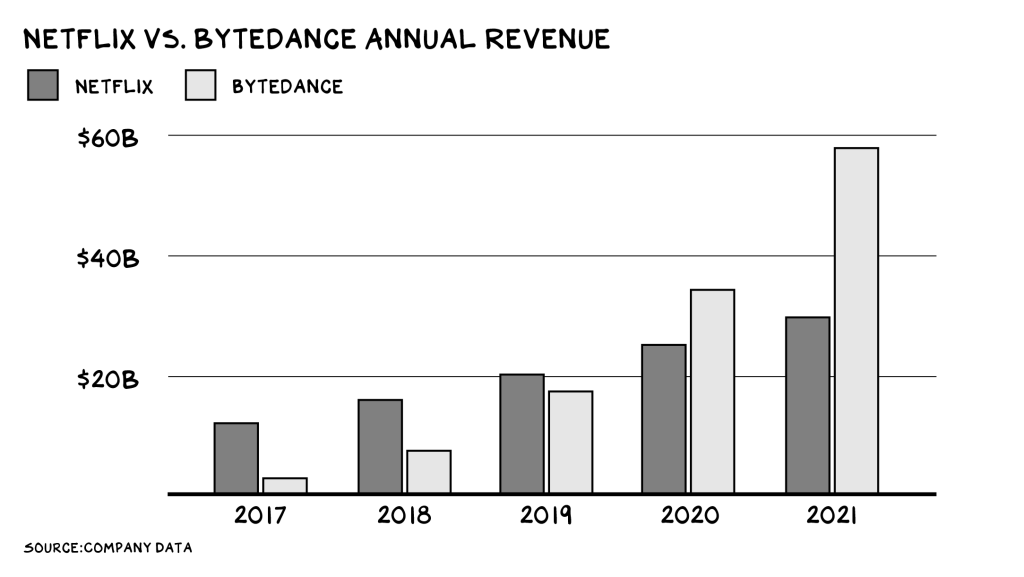

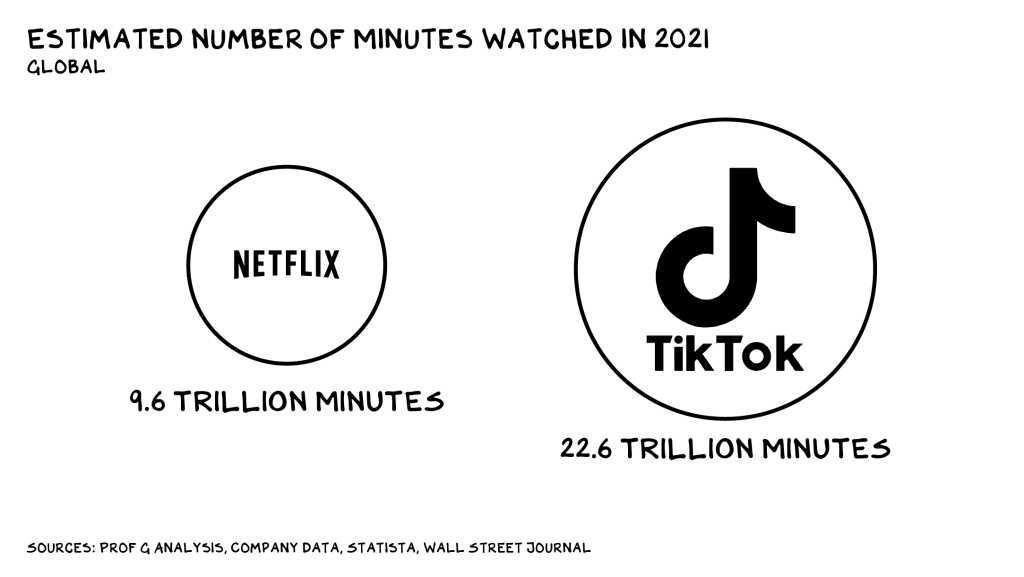

TikTok bills itself as a social media company, and the app is disrupting Meta by virtue of usurping attention. But that’s not all it’s doing. You can like, comment, and share, but these features exist as leverage points for one thing: watching videos. TikTok is a streaming platform, and the testicles being kicked over and over by TikTok belong to another company, Netflix. Over the past four years, ByteDance (parent company of TikTok) has gone from half the revenue of the original gangster of streaming to double. Six months ago Netflix was worth more than $300 billion — today it’s at $80 billion. And at its last valuation event, ByteDance was valued at, wait for it … $360 billion.

We’ve been watching the streaming wars for the past few years, but we were looking in the wrong place. “Video-based social media” was the Trojan horse. The gatekeepers of the content kingdom were being vanquished while we obsessed over subscriber growth at Disney+. The new occupant’s ascent to the Iron Throne was financed with a different currency — not monthly subscriptions or cable packages, but attention. Specifically, our youth’s attention.

Signal Liquidity

Facebook and Google also are using a new armament in their business war: data. You can sell data to advertisers to inform algorithms so their products and services are more attractive and addictive. But data on its own is a shapeless block. Signals are the mallets and chisels that bring form and utility to the algo. Anyway, if data is the new oil, algorithms are the refineries, and signals make the oil lighter, sweeter, and more valuable.

Cable is heavy, high-sulfur-content crude, as its only signals are weekly Nielsen ratings reports. Netflix gets signals directly, but just a few: what you watch, how long you watch, and whether you recommend the program. In aggregate, that data set can be refined into a powerful recommendation algorithm. But on a per-session basis, when we watch an average of two episodes, the number of signals registered from a typical user is likely no greater than six — so the refining process is slow, arduous work.

Then there’s TikTok, where the average session lasts 11 minutes and the video length is around 25 seconds. That’s 26 “episodes” per session, with each episode generating multiple microsignals: whether you scrolled past a video, paused it, re-watched it, liked it, commented on it, shared it, and followed the creator, plus how long you watched before moving on. That’s hundreds of signals. Sweet crude like the world has never seen, ready to be algorithmically refined into rocket fuel.

With great signal liquidity comes great content. Specifically, unique and personalized content. Netflix suggests 1980s war movies for me, which I knew I liked. What I didn’t know I liked: chiropractors confidently adjusting patients, hot people lecturing me on social justice issues, bloodhounds running in slow motion, and crocodiles ruining the days of befuddled animals looking for a drink of water. Watching Netflix is like going to Universal Studios Florida because you loved Disney. Watching TikTok is going on Safari.

Talent Liquidity

Just as algorithms require large pools of signals, content production requires large pools of talent. For a hundred years, video talent congregated in a few geographies: Los Angeles, Hong Kong, London, and Mumbai. Every HR manager knows there are talented people populating every corner of the Earth. But geography still matters, and the majority of platforms and talent do not find each other. YouTube and Instagram recruited talent faster than any business in history.

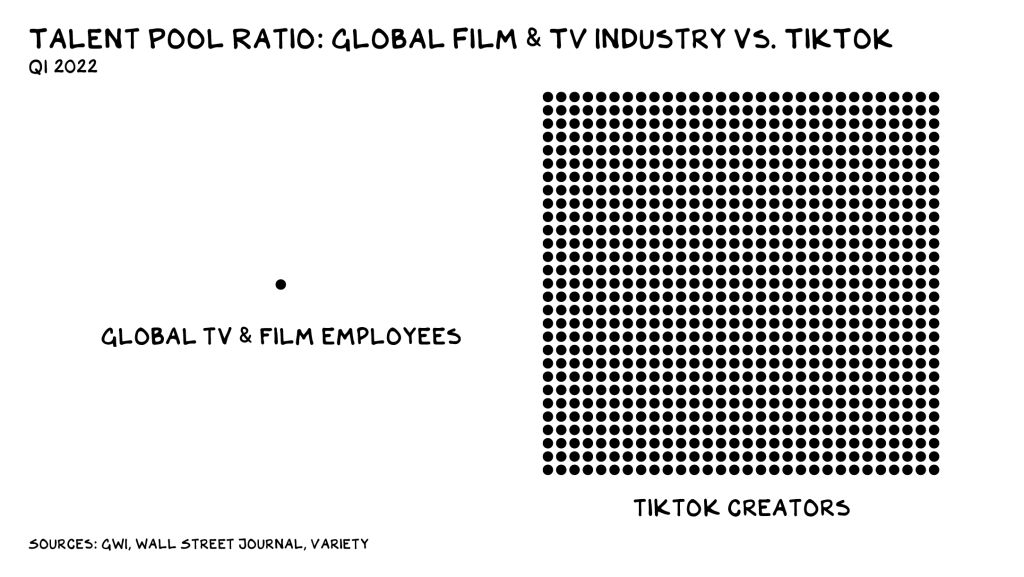

Until TikTok. 55% of TikTok users create their own videos on the platform. That’s a talent pool the depth of the Mariana Trench: 870 million people, or 1,000 times the number of people employed by the entire film and TV industry.

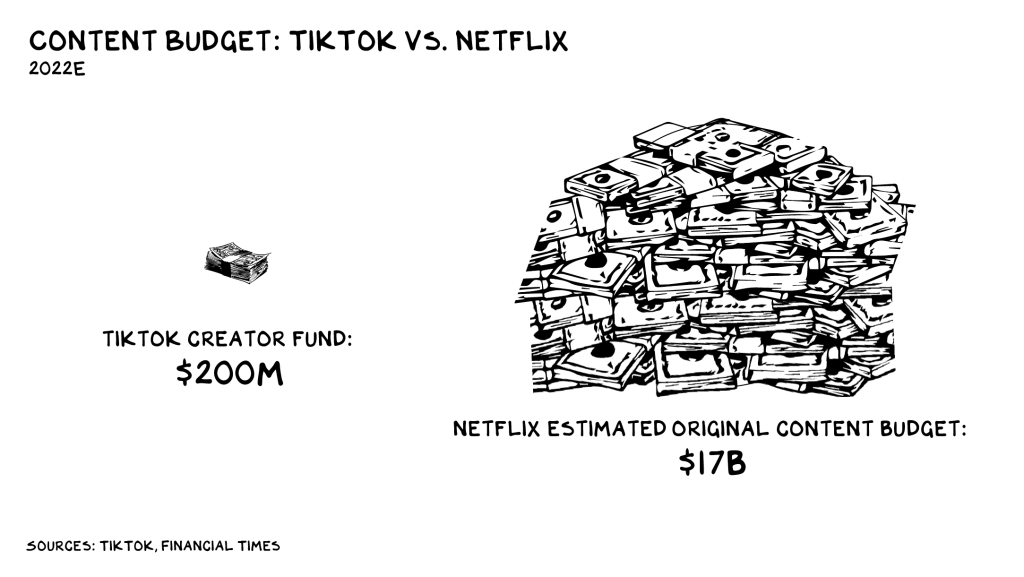

The world’s largest reserve of talent also has a near-zero cost of extraction. The top eight U.S. media firms will spend $115 billion on original content this year. Netflix alone will spend $17 billion.

TikTok produces its content for almost nothing — the company’s payout to top creators is a rounding error, at $200 million per year. The primary incentive it offers is social expression, and the company’s A&R team is the app itself. Users are never more than a few taps from creating their own content — TikTok streamlines the creation process, with an option to create a video at the center of its UI, simple tools for recording and manipulating those videos, and a huge library of licensed music available for the creator’s use. On YouTube and Netflix, there are creators and consumers. On TikTok, they are the same person.

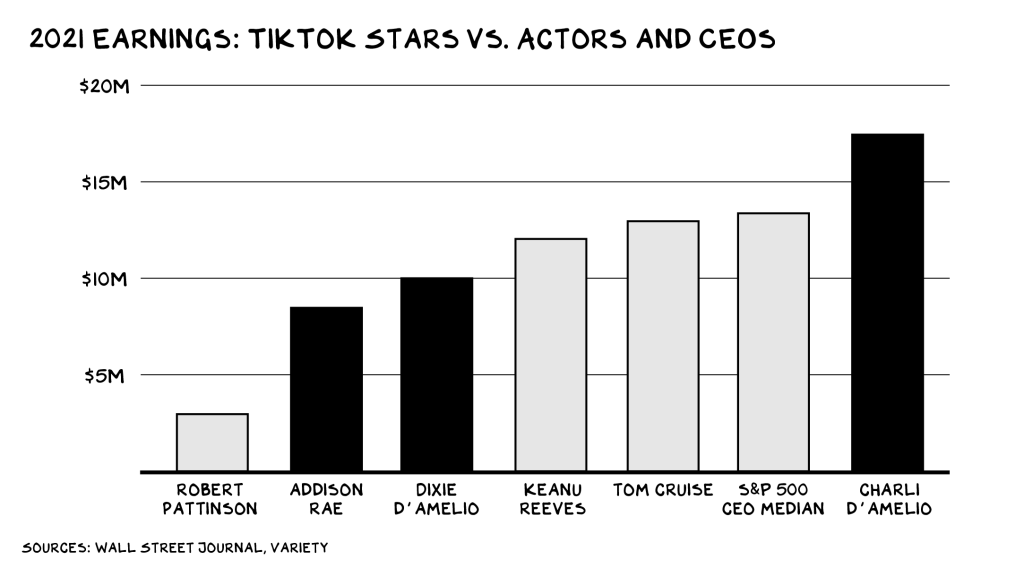

For creators who are in it for more than just expressing themselves, the real TikTok money comes from brand endorsements. And when your total addressable market is 1.6 billion users, your 15 seconds of fame on TikTok can be lucrative. The top creators make as much money as a Fortune 500 CEO or an iconic Hollywood actor.

I Don’t Know, You Pick

The average American adult makes 35,000 decisions every day — from what we wear to what size coffee we order. Each decision puts some degree of strain on our mental capacity. As the day goes on, we get tired and stop wanting to make decisions. It’s called decision fatigue.

The biggest mistake we make in marketing is believing choice is a benefit. No, it’s a tax. Consumers don’t want more choices, they want more confidence in the choices presented. TikTok has taken this to a new level by eliminating the burden of choice entirely. Its content is a continuous stream of videos where the decisions are made for you. Your only choice: what not to watch.

This creates a spiraling effect that welds people — especially young people — to the platform for hours. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for decision-making and impulse control, but this part of the brain doesn’t fully develop until the age of 25.

Surprise! Kids can’t stop watching TikTok.

NOTE: TikTok, to its credit, now reminds younger users to take breaks to go outside or get a snack. It also has creators who recommend all manner of books to read – a fact referenced by the latest bookstore owner consortium report which noted 100s of members had young readers coming in, asking for books recommended on TikTok.

This is an attempt to differentiate the brand from Meta, which has cemented itself as institutionally incapable of acknowledging or addressing the broader effects of its apps on society.

Risks

This attention-arbitraging streaming juggernaut shows no signs of slowing. But there are real risks that could interrupt the company’s trajectory to becoming one of the five most valuable businesses in the world.

For one, competition — TikTok products openly ripped-off by Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Snapchat, and Netflix. Of these, Facebook and Instagram are best positioned to compete thanks to Meta’s massive coffers of data and captive audience. But TikTok has years of short-form video data, as well as a grasp on the Holy Grail of social media: Kids think it’s cool. Zuckerberg is understandably anxious — Meta mentioned TikTok five times on its February earnings call.

Another risk is China, specifically the threat that the CCP could weaponize the platform — putting a gentle thumb on the algorithm, for example, to shape minds with content critical of America, capitalism, or the CCP’s detractors.

And then there’s regulation. This is the hallmark risk for corporate businesses, though in the U.S. it’s becoming increasingly irrelevant as its regulatory institutions continue to get derided and trampled and emasculated. Just recently I read that a federal judge in Florida told the CDC it couldn’t mandate the wearing of masks because they don’t “actively clean” the air, and another Federal court decided the SEC cannot enforce its own rules. Hoo, boy. But that’s for another post.

The externalities of any tech firm that grows this fast are severe, because these companies tend to blow by any stop signs as the speed blurs the license plate. Already, the app appears to be linked with eating disorders and depression, and it may even cause motor and verbal tics among teens. A threat to the well-being of our youth should logically be a catalyst for swift and severe action. It hasn’t happened. Don’t expect it to happen.

So, will TikTok become one of the most valuable companies in the world, or prove to be yet another tech firm whose profits and addictive qualities outpace our ability to govern it? The answer is likely … yes.