As the post-Roe era underscores the risks of digital surveillance, a new survey shows that teens face increased monitoring from their teacher – and the police.

Hey, America! How is all that data protection legislation and data-privacy-legislation-to-be working out for you?

BY:

Anthony Nicci

Cybersecurity Attorney / Reporter

PROJECT COUNSEL MEDIA

[ 🎩 tip to Ars Technica, the MWC, and Wired for allowing us to use their webinar notes ]

4 August 2022 (Washington, DC) – New technologies are expanding schools’ ability to keep students under surveillance – inside and outside the classroom – during the school year and after it ends. Schools have moved quickly to adopt a dizzying array of new tools. These include digital learning products that capture and store student data; anonymous tip lines encouraging students to report on each other; and software that monitors students’ emails and social media posts, even when they are written from home. Steadily growing numbers of police officers stationed in schools can access this information, compounding the technologies’ power.

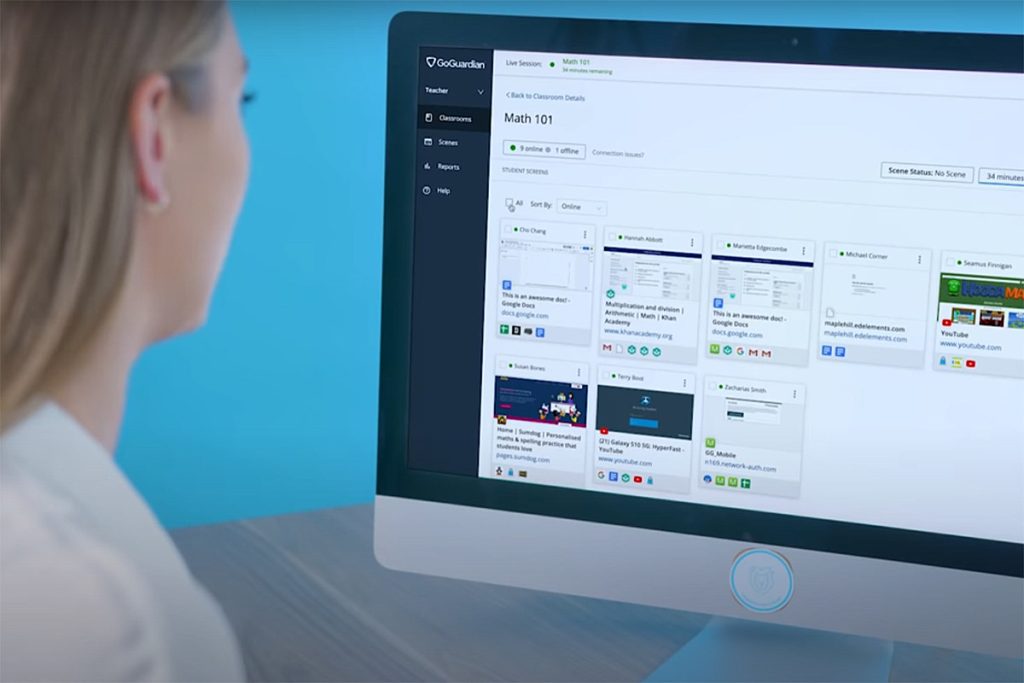

This is what high school teachers see when they open GoGuardian, a popular software application used to monitor student activity:

The interface is familiar, like the gallery view of a large Zoom call. But instead of seeing teenaged faces in each frame, the teacher sees thumbnail images showing the screens of each student’s laptop. They watch as students’ cursors skim across the lines of a sonnet or the word “chlorofluorocarbon” appears, painstakingly typed into a search bar. If a student is enticed by a distraction – an online game, a stunt video – the teacher can see that too and can remind the student to stay on task via a private message sent through GoGuardian. If this student has veered away from the assignment a few too many times, the teacher can take remote control of the device and zap the tab themselves.

For those of you who follow our series on COVID, student-monitoring software has merely come under renewed scrutiny after being examined during the pandemic. As we noted, when students in the US were forced to continue their schooling virtually due to the pandemic, many brought home school-issued devices. Baked into these machines is software that can allow teachers to view and control students’ screens, using quite quite sophisticated AI to scan text from student emails and cloud-based documents, and, in severe cases, send alerts of potential violent threats or mental health harms to educators and local law enforcement after school hours. Wired and Ars Technica covered this in detail in a series articles and several webinars during the COVID lockdowns.

But as the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) noted in a webinar yesterday (and detailed in this article), now that the majority of American students are finally going back to school in-person the surveillance software that proliferated during the pandemic will stay on their school-issued devices, where it will continue to watch them. The CDT report notes that 89 percent of teachers have said that their schools will continue using student-monitoring software, up 5 percentage points from last year. At the same time, the overturning of Roe v. Wade has led to new concerns about digital surveillance in states that have made abortion care illegal.

If you follow these developments via the media you know there are proposals targeting LGBTQ youth, such as the Texas governor’s calls to investigate the families of kids seeking gender-affirming care, which will raise additional worries about how data collected through school-issued devices will be weaponized this fall.

The CDT report also reveals how monitoring software can shrink the distance between classrooms and carceral systems. 42 percent of teachers reported that at least one student at their school has been contacted by law enforcement as a result of behaviors flagged by the monitoring software. And 37 percent of teachers who say their school uses activity monitoring outside of regular hours report that such alerts are directed to “a third party focused on public safety” (e.g., local police department, immigration enforcement). It is just a continuation of what we have been writing about for the last few years: schools have institutionalized and routinized law enforcement’s access to students’ information.

U.S. Senators have recently “raised concerns” (stand back! immediate action surely coming!) about the software’s facilitation of contact with law enforcement, showing the products will also be used to criminalize students who seek reproductive health resources on school-issued devices. The senators have sought responses from the 4 major monitoring companies used across the U.S. public school systems: GoGuardian, Gaggle, Securly, and Bark for Schools. The CDT report notes that those 4 companies reach thousands of school districts (there are 15,000 such districts) and millions of American students.

And, to be frank, the issues run deep. Widespread concerns about teen mental health and school violence lend a grim backdrop to the back-to-school season. After the mass shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, Congress passed a law that directs $300 million for schools to strengthen security infrastructure.

Not missing a moment to make some money, right after the law passed all 4 of the monitoring companies I noted above came out with press releases, speaking to educators’ fears, touting their products’ ability to zero in on would-be student attackers. During this weeks’ webinar, one presenter noted Securly’s website and press release which offers educators “AI-powered insight into student activity for email, Google Drive, and Microsoft OneDrive files. You can approach student safety from every angle, across every platform, and identify students who may be at risk of harming themselves or others”. Yep. Technology. The answer to every societal question.

Before the Roe decision brought more attention to the risks of digital surveillance, lawmakers and privacy advocates were already concerned about student-monitoring software. In March 2022, an investigation led by U.S. Senators Warren and Markey found that the four aforementioned companies – which sell digital student-monitoring services to K-12 schools – raised “significant privacy and equity concerns.” The investigation pointed out that low-income students (who tend to be disproportionately Black and Hispanic) rely more heavily on school devices and are exposed to more surveillance than affluent students; it also uncovered that schools and companies were often not required to disclose the use and extent of their monitoring to students and parents. In some cases, districts can opt to have a company send alerts directly to law enforcement instead of a school contact.

Students are often aware that their AI hall monitors are imperfect and can be misused. An investigation by The 74 Million found that Gaggle would send students warning emails for harmless content, like profanity in a fiction submission to the school literary magazine. One high school newspaper reported that the district used monitoring software to reveal a student’s sexuality and out the student to their parents. The CDT report revealed that 13 percent of students knew someone who had been outed as a result of student-monitoring software. And a Texas student newspaper’s editorial board argued that their school’s use of the software might prevent students from seeking mental health support. But, hey, news flash: surveillance always comes with inherent forms of abuse.

And worse. From the Wired webinar:

Also disquieting are the accounts of monitoring software breaching students’ after-school lives. One associate principal I spoke to says his district would receive “Questionable Content” email alerts from Gaggle about pornographic photos and profanities from students’ text messages. But the students weren’t texting on their school-issued Chromebooks. When administrators investigated, they learned that while teens were home, they would charge their phones by connecting them to their laptops via USB cables. The teens would then proceed to have what they believed to be private conversations via text, in some cases exchanging nude photos with significant others – all of which the Gaggle software running on the Chromebook could detect. Now the school advises students not to plug their personal devices into their school-issued laptops.

This pervasive surveillance has always been “disconcerting” to privacy advocates, but they know there is little they can do about it. And now that many states are moving to criminalize reproductive health care it will make all of these problems more acute. From the MWC webinar:

It’s not difficult to envision a student who lives in a state where ending a pregnancy is illegal using a search engine to find out-of-state abortion clinics, or chatting online with a friend about an unplanned pregnancy. From there, teachers and administrators could take it upon themselves to inform the student’s parent or local law enforcement.

So could the monitoring algorithm scan directly for students who type “abortion clinic near me” or “gender-affirming care” and trigger an alert to educators or the police? Gaggle’s PR department says “Gaggle’s dictionary of keywords does not scan for words and phrases related to abortion, reproductive health care, or gender-affirming health care”. BUT … Gaggle admitted that districts can ask Gaggle to customize and localize which keywords are flagged by the algorithm. The top tracking words relate to reproductive or gender-affirming health care.

Wired reporters went after GoGuardian, Bark for Schools and Securly and got:

GoGuardian: “As a company committed to creating safer learning environments for all students, GoGuardian continually evaluates our product frameworks and their implications for student data privacy. We are currently reviewing the letter we received from U.S. Senators Warren and Markey and will be providing a response”.

Bark for Schools initially agreed to speak to Wired, but the went silent.

Securly did not respond to 3 requests for comment.

Even if student-monitoring algorithms don’t actively scan for content related to abortion or gender-affirming care, the sensitive student information they’re privy to can still get kids in trouble with police. It is hardly a stretch to believe that school districts would be compelled to use the information that they collect to ensure enforcement of state law. In fact, many have been through the law enforcement ringer already. Schools can and do share student data with law enforcement. In 2020, The Boston Globe reported that information about Boston Public School students was shared on over 100 occasions with an intelligence group based in the city’s police department, exposing the records of the district’s undocumented students and putting those students at greater risk of deportation.

When it comes to safeguarding the privacy of students’ web searches and communications, current Federal protections are simply insufficient. The primary federal law governing the type and amount of student data that companies can slurp up is the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act. While FERPA has been updated a handful of times since it passed in 1974, it hasn’t kept pace with the technology that shapes reality for schools and students in 2022.

NOTE: the current national privacy bill in Congress (which might, in other respects, actually be good) won’t do anything for students either, as it excludes public institutions such as public schools and vendors that handle student data, and law enforcement agencies are seeking further carve outs.

My wife teaches at the high school level here in the U.S. It is a short term gig (2 years), for the Advanced Placement program in the Italian language. Her fellow teachers says educators have shouldered unprecedented responsibility of helping students recover from two extremely disruptive years while providing mental health support in the wake of campus tragedies. The monitoring companies’ websites share stories of their products flagging students’ expressions of suicidal ideation, with testimonies from teachers who credit the software with helping them intervene in the nick of time. So she says the monitoring has received a mixed response from teachers. And, obviously, especially after school shootings, educators are understandably fearful.

But the evidence that monitoring software actually helps prevent violence is scant. Data privacy advocates are arguing that forcing schools to weigh surveillance against safety perpetuates a false choice. As I noted above, surveillance always comes with inherent forms of abuse. But as a technical expert noted during one of the webinars, schools would need to undergo a rigorous student privacy rubric to measure all software they would be using with students. The rubric would need to include items like whether the student’s data was disposed of and whether it was shared with other parties. It is a difficult process – and costs serious money, and expertise.

I’ll end with that technical expert’s evaluation:

You need to be wary of the promises student-monitoring companies make. The systems provide A) a false sense of security, and B) kills the curiosity that you want to inspire in learning. If you’re going to rely on a technology system to tell you a kid’s unhappy, that’s concerning to me because you’re not developing relationships with kids who are in front of you. And as to the companies’ claims about bolstering safety and anticipating school violence … ridiculous. There’s no single answer to these incredibly complex issues. This ‘We’re gonna be able to predict that sort of thing’ is just bullshit. But, this is America. It is now in our DNA that technology is the panacea to everything”.